|

Upon his retirement, Richard A. Posner, Judge, 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, Chicago, Illinois, reflected on how most judges view and treat pro se litigants

|

An Exit Interview With Richard Posner, Judicial Provocateur

WASHINGTON — Judge Richard A. Posner, whose restless intellect, withering candor and superhuman output made him among the most provocative figures in American law in the last half-century, recently announced his retirement.

The move was abrupt, and I called him up to ask what had prompted it.

"About six months ago," Judge Posner said, "I awoke from a slumber of 35 years." He had suddenly realized, he said, that people without lawyers are mistreated by the legal system, and he wanted to do something about it.

|

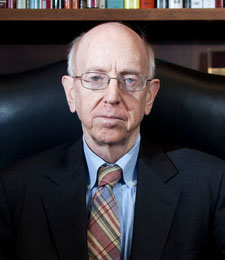

Judge Richard A. Posner said he realized that people without lawyers are mistreated by the legal system, and he wanted to do something about it. Photo credit: Nathan Weber, The New York Times |

For starters, as is his habit when his interest alights on a fresh topic, he wrote a book on the subject. Judge Posner blurts out books at a comic pace.

"I realized, in the course of that, that I had really lost interest in the cases," he said. "And then I started asking myself, what kind of person wants to have the same identical job for 35 years? And I decided 35 years is plenty. It's too much. Why didn't I quit 10 years ago? I've written 3,300-plus judicial opinions."

He is 78 and had been a judge since 1981, when President Ronald Reagan appointed him to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, in Chicago. Before that, he was a prominent law professor who was among the leading figures in the movement to analyze legal problems using economics. In emphasizing social utility over, say, principles of fairness and equality, he gained a reputation as a cold, calculating conservative.

That changed over time, and his recent opinions on voter ID laws, abortion, same-sex marriage and workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation have been decidedly liberal.

"The things I used to be interested in — economic issues in the law, for example — they don't play a big role in the work of this court," Judge Posner said. "Gradually, those interests sort of fell by the board."

He wrote books about law and literature, sex and reason, the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, the 2000 election recount and, after the Sept. 11 attacks, national security.

"Gradually, I lost interest or exhausted my interest," he said. "So for the last 10 or 15 years, I've just been focused on the court."

He called his approach to judging pragmatic. His critics called it lawless. "I pay very little attention to legal rules, statutes, constitutional provisions," Judge Posner said. "A case is just a dispute. The first thing you do is ask yourself — forget about the law — what is a sensible resolution of this dispute?"

The next thing, he said, was to see if a recent Supreme Court precedent or some other legal obstacle stood in the way of ruling in favor of that sensible resolution. "And the answer is that's actually rarely the case," he said. "When you have a Supreme Court case or something similar, they're often extremely easy to get around."

I asked him about his critics, and he said they fell into two camps.

Some, he said, simply have a different view of the proper role of the judge. "There is a very strong formalist tradition in the law," he said, summarizing it as: "Judges are simply applying rules, and the rules come from somewhere else, like the Constitution, and the Constitution is sacred. And statutes, unless they're unconstitutional, are sacred also."

"A lot of the people who say that are sincere," he said. "That's their conception of law. That's fine."

He said he had less sympathy for the second camp. "There are others who are just, you know, reactionary beasts," he said. "They're reactionary beasts because they want to manipulate the statutes and the Constitution in their own way."

The immediate reason for his retirement was less abstract, he said. He had become concerned with the plight of litigants who represented themselves in civil cases, often filing handwritten appeals. Their grievances were real, he said, but the legal system was treating them impatiently, dismissing their cases over technical matters.

"These were almost always people of poor education and often of quite low level of intelligence," he said. "I gradually began to realize that this wasn't right, what we were doing."

In the Seventh Circuit, Judge Posner said, staff lawyers rather than judges assessed appeals from such litigants, and the court generally rubber-stamped the lawyers' recommendations.

Judge Posner offered to help. "I wanted to review all the staff attorney memos before they went to the panel of judges," he said. "I'd sit down with the staff attorney, go over his memo. I'd make whatever editorial suggestions — or editorial commands — that I thought necessary. It would be good education for staff attorneys, and it would be very good" for the litigants without lawyers.

"I had the approval of the director of the staff attorney program," Judge Posner said, "but the judges, my colleagues, all 11 of them, turned it down and refused to give me any significant role. I was very frustrated by that."

His new book, he said, would have added to the tension: "If I were still on the court, it would be particularly awkward because, implicitly or explicitly, I'm criticizing the other judges."

Judge Posner said he hoped to work with groups concerned with prisoners' rights, with a law school clinic and with law firms, to bring attention and aid to people too poor to afford lawyers.

In one of his final opinions, Judge Posner, writing for a three-judge panel, reinstated a lawsuit from a prisoner, Michael Davis, that had been dismissed on technical grounds. "Davis needs help — needs it bad — needs a lawyer desperately," he wrote.

On the phone, Judge Posner said that opinion was a rare victory. "The basic thing is that most judges regard these people as kind of trash not worth the time of a federal judge," he said.

From: Adam Liptak, "An Exit Interview With Richard Posner, Judicial Provocateur," The New York Times, September 11, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/11/us/politics/judge-richard-posner-retirement.html, accessed December 2, 2017. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C.

- Following his retirement from the bench, Judge Posner went on to found the Posner Center of Justice for Pro Se's, a non-profit foundation (http://www.justice-for-pro-ses.org/preview.pdf) that provides assistance or guidance to pro se litigants who wish to represent themselves in state or federal court.

- In 2019, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida prepared a guide for pro se filers that contains useful information generally applicable to other district courts.

|

THE ANTI-PRO-SE JUDICIARY

|

|