|

Activist Wants to See Judges Judged

JESSICA GARRISON

April 24, 2006

For years, Ron Branson toiled in his North Hollywood garage in lonely isolation, repeatedly failing to gather enough signatures to put on California's ballot a constitutional amendment that would make it much easier to investigate, sue and oust judges.

Then, last fall, the minister and former prison guard — who has repeatedly sued the government and who said he once appealed a parking ticket all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court — set his sights on a smaller target. Connecting with a feed equipment manufacturer in South Dakota, Bill Stegmeier, who kicked in a mere $140,000 (as opposed to the $1 million-plus it would likely cost in California), he collected enough signatures to put an amendment before voters in that state. (Stegmeier has since distanced himself from Branson.)

That amendment, which Branson says he hopes will soon be copied nationwide, would create grand juries with the power to investigate and indict judges, as well as toss them off the bench and strip them of their immunity so they could be sued for decisions they make. He calls it the Judicial Accountability Initiative Law, which shortens to the catchy slogan "JAIL for Judges."

Quite suddenly, Branson — an idiosyncratic populist who calls himself the Five-Star National JAIL Commander in Chief and affixes five metal stars to his lapels — found he had captured the attention of judges and lawmakers across the country.

They say his plan is a terrible idea and represents nothing less than an attack on the premise of a fair and impartial judiciary that operates independently of pressure from special interests. That's because if judges can be investigated, sued and even jailed for decisions they make, few will be likely to make unpopular decisions, even if that is what the law calls for.

"I view efforts such as these as threats to our democratic government," said the chief justice of California's Supreme Court, Ronald M. George, who has begun speaking out against JAIL. Missouri's chief justice has issued similar warnings. And in South Dakota, the Legislature unanimously voted to condemn Amendment E, which will be on the ballot in November.

|

|

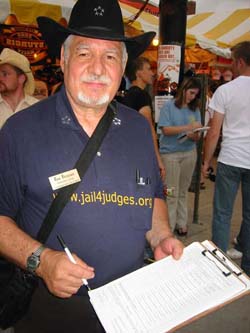

Ron Branson of Los Angeles, collecting signatures in Sturgis, South Dakota for the South Dakota Judicial Accountability Initiative Law (J.A.I.L.).

Photo courtesy of Bill Harlan, Rapid City Journal, August 8, 2005. |

|

Some opponents also pointed out that California and other states already have ways to investigate complaints against judges.

Which is not to say that those mechanisms are perfect. Federal judges, for example, are appointed for life and are rarely removed.

"Everyone knows who the abusive federal judges are and almost nothing happens," said Steven Lubet, a law professor at Northwestern University and a co-author of the book "Judicial Conduct and Ethics."

In California, state judges are subject to retention elections and can also be disciplined by the Commission on Judicial Performance, but some have complained that the commission is not as proactive as it should be.

Last year, for example, the panel admonished a judge who invited a rape victim who appeared in his court to have a private dinner with him.

At the time, lawyers complained that Judge John D. Harris's misbehavior had been known for years and the panel took too long to act.

"Judicial discipline is a very touchy issue," Lubet added. "No system works perfectly. You have to either over-discipline or under-discipline."

He added that because judges "need to protect the powerless against the powerful," it is "reasonable to err on the side of under-discipline, because the alternative is an intimidated judiciary."

Branson is fond of quoting the Constitution and professes disdain for lawyers even as he proudly declares that he has been compared to one. He says more stringent measures are necessary because the judiciary is an unchecked power run amok, and is incapable of policing itself.

"The law on the books," he writes in his autobiography, which is posted on the JAIL for Judges website, is "a facade to give the public the impression that we had laws that governed our society."

Branson's crusade had modest beginnings: an encounter with the LAPD over a parked car in Canoga Park.

Branson and his wife said they thought the car was abandoned, and were looking at it. The LAPD arrested him on suspicion of burglary. He spent six days in jail, during which time he was hit with a Taser, he said.

He reacted to this event as he would to other grievances over the years: He filed a lawsuit in state court, seeking $13.5 million from the city of Los Angeles and the LAPD.

The lawsuit went nowhere, and Branson claims that the judge failed to enter the judgment properly, making it difficult for him to appeal. The Bransons believe that there was a conspiracy between the judge and the city. Branson also tried to sue in federal court. That attempt was rebuffed. He finally concluded, he said, that the system was "an absolute fix with no possibility of redress."

And so over two days in 1995, he sat down and wrote a manifesto called "The Judicial Reform Act of 1996" — the first of three attempts to place a constitutional amendment on the California ballot.

By this time, he had teamed with a Valencia lawyer, Gary Zerman, who was also steamed over the doctrine of judicial immunity.

The two formed JAIL for Judges. They attracted supporters in all 50 states — although, despite its military-style structure, the organization does not always run like a well-oiled machine.

Subsequently, the South Dakota movement separated from JAIL for Judges, according to Bonnie Russell, a spokeswoman for the Amendment E campaign. Russell said Branson is a publicity hound who is bad for the campaign because he comes across as "a clown." The opposition in South Dakota is using him to discredit the movement, she said.

Branson said that Russell is trying to "appease" and "play footsies" with people in South Dakota opposed to the amendment and is also trying to hide the fact that he is from California.

Court watchers, however, have stopped laughing.

"It has to be taken seriously because the organizers did get it on the South Dakota ballot," said Bert Brandenburg, executive director of the Justice at Stake Campaign, a national organization that pushes for fair and impartial courts. "One of the effects of passing one of these measures would be to throw the door wide open for interest groups to come in and pressure courts into ruling on behalf of special interests instead of the public interest. ... It would be a driver's license for anti-court people around the country."

Branson agrees. He says there is talk of moving on to Nevada, Oregon, Florida, and, of course, of returning to California.

"When I started this thing, I had no money and no volunteers. I knew the Lord called me to do it. I figured I got to get out there and do it," he said. "I am informed that if we win in South Dakota, there will be millions for us."

Copyright 2006, Los Angeles Times

Text from: Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, California, April 24, 2006, Home Edition, p. B-1. Reprinted in accordance with the "fair use" provision of Title 17 U.S.C. § 107 for a non-profit educational purpose.

|